“The worst is yet to come.”

That’s the self-explanatory title of Nomura’s latest analysis assessing the consequences from the coronavirus pandemic, and which comes just two weeks after the Japanese bank issued its first preliminary assessment on the fallout from the global pandemic, which as readers will recall we found unduly optimistic. Well, a lot has happened since then, and as the report’s title suggests, the outlook has deteriorated sharply.

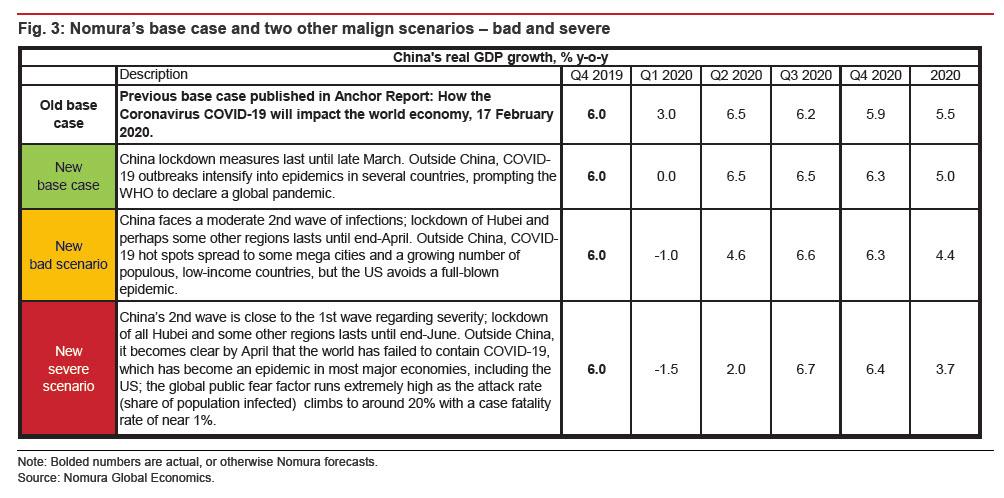

In the bank’s new base case, it revises down further its Q1 2020 GDP growth forecast for China to 0% y-o-y, and for the world to 0.9%. While Nomura still envisages a V-shaped global recovery in Q2 in its new base case, it now has a “U” in its new “bad scenario” and a downright depressionary “L” (non) recovery in the new severe scenario.

Below are the details on how in just two short weeks, the situation went from bad to downright catastrophic, in the bank’s own words:

- The positive news is the marked decline in the number of new daily confirmed COVID-19 cases in China, but it has also demonstrated the challenging trade-off other governments now face between public health security controls – ranging from adequate resources of health services to containment and mitigation measures – and economic growth.

- China imposed draconian controls, sealing off Hubei’s nearly 60m inhabitants, blocking transport and locking down dozens of cities. China’s authoritarian state may have won the battle against the virus but at a huge short-run cost to economic growth. Our new base case assumes that China’s lockdowns end late this month, which will be too late to avoid our forecast of GDP growth slowing to 0% y-o-y this quarter, which translates to -4.4% q-o-q.

- This contraction in China’s economy will have major negative spillover effects on the rest of the world, particularly in the rest of Asia – and this is only just starting to show up in the economic data. However, what has really spooked financial markets is the rapid contagion of COVID-19 outside China to 76 countries (and counting), with a handful of hotspots – South Korea, Italy and Iran. These hotspots are now experiencing the same severe simultaneous demand (public fear factor) and supply (business disruption) shocks as China in addition to the negative spillover effects from China’s contracting economy.

- While COVID-19 has not been as deadly as SARS (the case fatality outside China and Iran is 1.5% vs 10% for SARs), what is now clear is that it spreads much more easily. As COVID-19 spreads, governments will need to weigh the trade-off between health security and economic growth and it remains to be seen whether they have the resources and wherewithal to increase their health security controls – and the public’s willingness to follow them – to the same force and effectiveness as China has done. If not, the rest of the world could, in the not too distant future, lose control in trying to contain COVID-19.

Separately, for those urging for a central bank response, Nomura’s economists caution that in this abnormal economic slump, “macroeconomic policies are less well equipped to help (or “can only help so much”). If health security controls fail to contain the spread of COVID-19, financial markets may soon have to accept that a global recession is a forgone conclusion.”

In short, the situation is bad, and could get much worse if the pandemic spreads unchecked even faster around the globe.

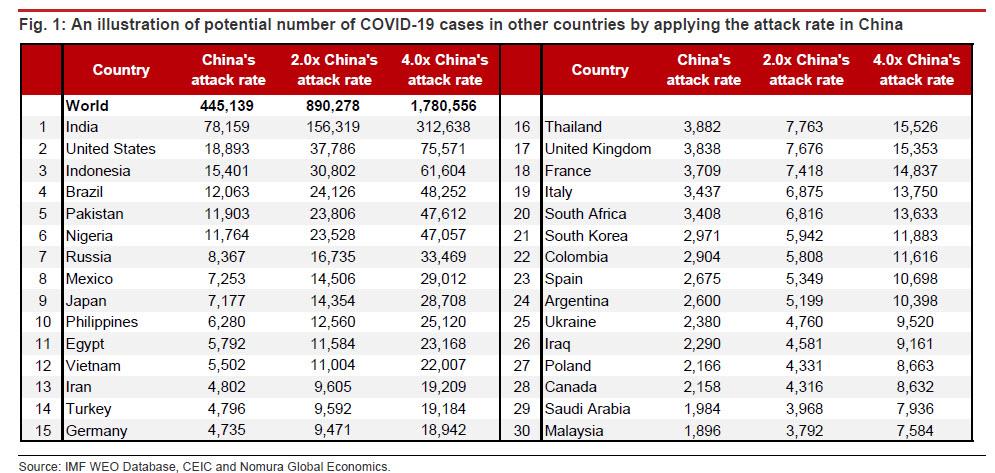

How much worse? To consider the magnitudes, Nomura crudely assumes COVID-19’s attack rate (the percent of the population infected) in the rest of the world ends up being, on average, similar to that in China – then number of world confirmed cases could peak at 445,000. But if the rest of the world’s security controls are half as rigorous (the attack rate is twice as high as China’s) the number of world confirmed cases could peak at 890,000, and if world’s controls are one-quarter as rigorous, the peak could be 1.78m.

Consider the 2009 H1N1 Influenza. It started in the US in late April 2009 and spread with great intensity. By 11 June, it had reached 74 countries with a total of 30,000 cases and it was on this date that the WHO declared a global pandemic (it has not declared one since); by early November it has reached over 200 countries with 0.5m cases. We estimate that over the same period since the initial outbreak, the number of COVID-19 cases is about 3x more than 2009 H1N1, and if it tracks the 2009 H1N1 case trajectory there could be 1.5m COVID-19 cases by June 2020.

* * *

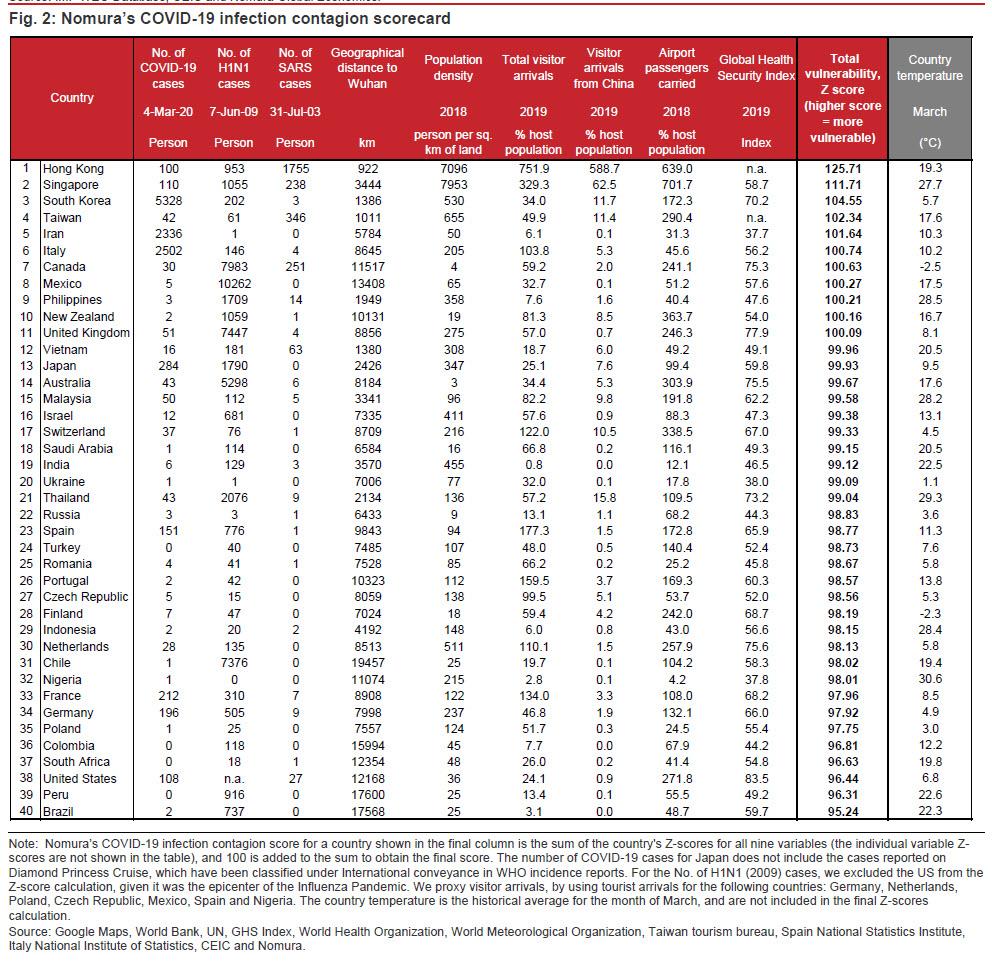

Extending on the above analysis, to get a relative sense of which countries outside China are most vulnerable to becoming high infection hotspots from COVID-19, Nomura has expanded the scorecard in our earlier Anchor report to 40 countries (Figure 2). Of the nine indicators, higher values indicate a higher risk of contagion, except in the case of geographical proximity and the global health security index, where lower values indicate higher vulnerability. The bank then normalizes the values of each of the nine indicators across countries, by calculating Z-scores, and sums up the nine Z-scores for each country and add 100. The results line up reasonably well with the COVID-19 contagion so far with South Korea, Iran and Italy ranking as highly exposed.

Glancing at country temperatures, there is support for the notion that COVID-19 is weaker in warmer climates, but the analysis shows several countries with mild temperatures that are at risk of becoming hotspots. The two most exposed – Hong Kong and Singapore – have been relatively successful in containing COVID-19 so far.

And while there is much more in the full 64-page analysis, we can summarize the analysis with the following three somber warnings:

- The COVID-19 shock is quickly morphing into a global crisis. In addition to major economic spillover effects from China’s large GDP contraction in Q1, an increasing number of countries are having to contend with their own local demand and supply-side shocks from the spread of COVID-19, plus a tightening in global financial conditions.

- In terms of rapid policy response, the Fed is really the only game in town (we expect the Fed to cut rates by a further 50bp in our base case and 125bp in our bad scenario). The ECB and BOJ have limited room, and fiscal stimulus will take time to deploy.

- This is an abnormal global economic slump. The most effective immediate policy response is not monetary or fiscal policies; it’s health security controls. If health security controls fail to contain the spread of COVID-19, financial.