“When the federal statutes speak of ‘the election’… they plainly refer to the combined actions of voters and officials meant to make a final selection of an officeholder… By establishing a particular day as ‘the day’ on which these actions must take place, the statutes simply regulate the time of the election, a matter on which the Constitution explicitly gives Congress the final say.” Foster v. Love, 522 U.S. 67, 71-72 (1997)

We will take a closer at this binding precedent below, but in preview, please understand that it emanates from a 9-0 decision of the United States Supreme Court, wherein the entire Court joined, not just the outcome, but also the opinion on this very point.

The voters vote. The officials count. These combined actions form “the election,” and the election must be decided on the day. States that failed to make a final selection of officeholder by midnight after Election Day have violated the statute, subjecting the nation at large to the very evils Congressionally mandated deadlines were drafted to prevent.

Federal Election Day statutes were designed to curtail fraud, and to infuse a prima facie sense of integrity in our electoral process. But these States – in failing to obey Congressional deadlines – have flagrantly attempted to preempt federal law. This is certainly prohibited, and this is why the late election results are void.

Citizens may file actions in the Federal District Courts and appeal all the way to the Supreme Court. Get this information to your State Representatives and Senators. Forward it to the White House if you know anyone with connections. Blog it. Video it. Podcast it. Share it in comments, please. The President’s team has not made this argument yet. They have not plead it. And they must get up to speed.

You were disenfranchised by the failure of States to follow federal law.

Your pursuit of happiness is directly infected. You have a cause of action.

This is the peaceful, legal battle plan of the Republic. Let’s roll.

THE FINESSE

Suspend disbelief. I’m not stretching on that headline. I honestly do not believe the Supreme Court can avoid nullifying the Presidential Election… if President Trump, and some of you too, will plead this in court.

My previous report discussed the plenary authority of State Legislatures to determine how Presidential Electors are appointed. Consider this Part 2. (Review Part 1. Now.)

3 U.S.C. § 2 kicks the decision back to the State Legislatures after a failed election renders the previous results void. Failed elections nullify all votes, not just some votes, not just late votes, not just illegal votes. The election itself is void in late States.

Which States are late? The answer will be a question of first impression for the Supreme Court. But the only fair answer is obvious. If, at midnight, one candidate had enough of a lead, so that there was no mathematical possibility whatsoever of their being caught – after a review of the votes already counted, and the votes remaining – then the final selection has been made on time. But if the outcome was uncertain at Midnight, the State violated the deadline, and its election is void.

This hard mathematical rule will motivate States to develop better comprehensive procedures, and to commit sufficient monetary resources to safeguard our elections from despair going forward. Perfect elections are possible, and developing them is a fundamental purpose of paying taxes. We are a wealthy nation. Get it right.

As to Representative and Senate races, the statutes mandate subsequent elections, but as to presidential electors, 3 U.S.C. § 2 provides a deadline extension to the State Legislatures alone to determine – “in such manner as the legislature of such State may direct” – which electors shall be appointed. This statute simply reiterates the plenary authority in the United States Constitution.

We should find out soon what the State Legislatures will do, because the United States Supreme Court is about to nullify the results of this election in every State that failed to report a clear winner before November 4th.

WHAT ABOUT BUSH V. GORE?

At this point, you may be wondering, if my analysis above is correct, why the election in Bush v. Gore wasn’t void? It’s a very good question. That nightmare dragged on for 37 days, finally settled by a nebulous opinion, just as the Florida Legislature was getting ready to use the nuclear option to seat Bush electors via bicameral resolution. Incredibly, the answer to this very relevant question is shockingly simple:

That election wasn’t void because nobody asked the court to void it.

Question: Why would Congress create the “safe harbor” protections listed in 3 U.S.C § 5, if not for settling election contests by State statutes that call for multi-day recounts? Doesn’t 3 U.S.C. § 5 imply that Congress condones presidential elections extending past the Midnight deadline?

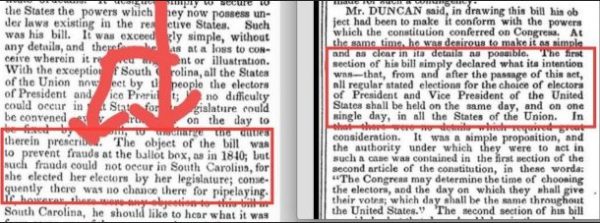

Answer: No, it does not. Rather than condoning late elections, it condemns them. 3 U.S.C. §1 was specifically designed to prohibit multiday elections. See the graphic below (Congressional Globe, 28th Cong., 2d Sess., at 14, December 9, 1844 (Mr. Duncan)), where both the “intention”, and the “object, of the bill were stated:

“The first section of his bill simply declared what its intention was—that, from and after the passage of this act, all regular stated elections for the choice of electors of President and Vice President of the United States shall be held on the same day, and on one single day, in all the States of the Union.”

“The object of the bill was to prevent frauds at the ballot box as in 1840; but such frauds could not occur in South Carolina, for she elected her electors by her legislature; consequently there was no chance for pipelaying.”

Pipelaying. Indeed:

“Congress in 1844 and 1845 was, however, concerned about the allegations of fraud and corruption in the previous election (1840) for electors for President and Vice President in several states. It was asserted that some of the particular misconduct in that election appeared to have been encouraged, in part, because the states had differing dates for the presidential election, which allowed the alleged movement of populations and voters to key states having later elections (described as ‘pipelaying’)”. (U.S. Congressional Research Service. Postponement and Rescheduling of Elections to Federal Office (RL32623; Sept. 5, 2014)

I think Georgia is getting ready for some pipelaying in Senate run-offs.

3 U.S.C. § 5 was unfortunately misconstrued by the Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore, because the safe harbor statute should only be applied as to disputes within a State Legislature. That branch alone has plenary authority to determine who the State appoints as electors. If there is no dispute in the Legislature, their chosen slate of electors must be appointed by the State. Therefore, the only “State authorities” who may engage Constitutionally in such a controversy are Representatives and Senators.

State elections that fail to choose winners by the Midnight deadline enacted in 3 U.S.C. § 1, immediately trigger the authority of 3 U.S.C. § 2, giving the Legislatures alone a Congressional extension to choose electors thereafter. As such, the failed elections are void, and all State statutes drafted to discern a winner after Election Day are preempted by 3 U.S.C § 1, and § 2.

Having plenary authority, there can only be a controversy between the State House and Senate, should the House choose one slate of electors, and the Senate a different slate. The safe harbor of 3 U.S.C. § 5 will treat as conclusive a determination guided be previous State law, if such law is enacted prior to Election Day to settle this specific dispute, and the determination is made at least six days before the safe harbor date. But if there is no State law to cover a bicameral dispute, 3 U.S.C. § 15, gives explicit instructions how to proceed.

The evidence of the veracity of this analysis is located in the very text of 3 U.S.C § 15:

“[B]ut in case there shall arise the question which of two or more State authorities determining what electors have been appointed, as mentioned in section 5 of this title, is the lawful tribunal of such State…”

As to the choosing of presidential electors, only two possible tribunals have authority to choose according to the United States Constitution; the State House of Representatives; or, the State Senate. If the controversy between them is not settled by the safe harbor in section 5, then section15 provides that the two houses of federal Congress will decide, and if they are split, then the determination is made by the slate of electors certified by the Governor acting as a tie breaker. This is why section 15 contemplates “two or more State authorities” sending different slates. You could also imagine that various plurality cliques of Representatives and Senators might form, causing any number of slates to be forwarded.

However, I’m not convinced at all that 3 U.S.C § 5, and, 3 U.S.C. § 15, are Constitutional. I don’t see where the Constitution gives Congress any authority to determine the manner of choosing presidential electors, while these sections both do exactly that. Congress has plenary authority over the time, and none as to the manner.

JUDICIAL RESTRAINT

Courts exercise judicial restraint by refraining to alter pleadings or grant relief not sought therein. This principle is firmly embedded in our system of Government, and the Supreme Court recently restated this principle in April, when it shut down the Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, after that bench extended the presidential primary voting deadline by six days. Justice Kavanaugh wrote the opinion:

“[T]he plaintiffs themselves did not even ask for that relief in their preliminary injunction motions. Our point is not that the argument is necessarily forfeited, but is that the plaintiffs themselves did not see the need to ask for such relief. By changing the election rules so close to the election date and by affording relief that the plaintiffs themselves did not ask for in their preliminary injunction motions, the District Court contravened this Court’s precedents and erred by ordering such relief. 140 S. Ct. 1205, 1207 (2020).

(This case concerned a primary, not a general election for presidential electors. And so the State was not constrained by the Midnight deadline set forth in the federal Election Day statute, 3 U.S.C. § 1, but only by previously enacted State law.)

Success in the law is based on using magic words. It really is. If you don’t use them, the court has no obligation to fix your pleadings. But if you know the spell, and you know how to cast it on paper, miracles can happen. Revolutionary arguments surface even when long standing practices appear to have firm judicial support.

In this case, the preempted behavior was failing to decide the elections “on” Election Day. Presidential electors must be appointed by midnight on Election Day, not at some ever changing time untamed by federal reach. We have a Congressional statute which is completely unambiguous, but it’s never enforced in Presidential Elections. Regardless, a terrible habit doesn’t nullify a good law.

The elections for President in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Georgia, Arizona, Wisconsin and Nevada were void at the stroke of midnight after Election Day, because a victorious candidate wasn’t discerned by Midnight.

I’m writing this on November 17, 2020, and just yesterday they found over 2600 missing votes in Georgia with most of the state still recounting a razor thin contest. In Arizona, they are still conducting the initial canvass, and for some reason they appear only capable of handling a few hundred votes a day, which is bizarre, compared to the rest of the country. It certainly doesn’t inspire confidence. A potential recount in Wisconsin was triggered by another close result. The Legislatures in Wisconsin and Michigan are investigating irregularities. Pennsylvania is a disaster. 8000 votes were just “discovered” today.

Houston, we have a statutory problem.

THE PRECEDENT: Foster v. Love, 522 U.S. 67 (1997)

In 1975, Louisiana employed a new statutory process for electing United States Senators and Representatives. In October of a federal election year, the State held open primaries for congressional offices. All candidates, regardless of party, appeared on a general ballot, and the voters, despite party affiliation, voted for any candidate. If no candidate for an office received a majority of the vote, the State held a run-off election the following month on federal Election Day, between the two candidates who received the most votes. But if a candidate did gather a majority in the primary, there was no further election on Election Day, and therefore no voting for that office on the day.

In a unanimous, 9-0 decision, the Supreme Court struck the Louisiana statute down, as it was preempted by 3 U.S.C. § 1, and therefore in violation of the Constitution’s plenary grant of authority to Congress to determine the time of Congressional elections.

Pardon the repetition, but we need to see this quote in its proper context:

“When the federal statutes speak of ‘the election’ of a Senator or Representative, they plainly refer to the combined actions of voters and officials meant to make a final selection of an officeholder… By establishing a particular day as ‘the day’ on which these actions must take place, the statutes simply regulate the time of the election, a matter on which the Constitution explicitly gives Congress the final say.

“While true that there is room for argument about just what may constitute the final act of selection within the meaning of the law, our decision does not turn on any nicety in isolating precisely what acts a State must cause to be done on federal election day (and not before it) in order to satisfy the statute. Without paring the term ‘election’ in § 7 down to the definitional bone, it is enough to resolve this case to say that a contested selection of candidates for a congressional office that is concluded as a matter of law before the federal election day, with no act in law or in fact to take place on the date chosen by Congress, clearly violates § 7.4″.

Footnote 4 from the opinion is cued up here, and it’s crucial to our point:

“4. This case thus does not present the question whether a State must always employ the conventional mechanics of an election. We hold today only that if an election does take place, it may not be consummated prior to federal election day.”

That was the main holding; an election that is consummated – which means decided, over, done – before Election Day, is preempted by the federal Election Day statute. Also note that – while the Court refused to decide exactly what may constitute the acts necessary to make the selection final – the State “must cause” those acts “to be done on federal election day.”

Question: How is Foster v. Love controlling with regard to Presidential Elections that are completed after Election Day?

The opinion says the following about presidential elections:

[The] congressional rule adopted under the Elections Clause (and its counterpart for the Executive Branch, Art. II, § 1, cl. 3) sets the date of the biennial election for federal offices, as “[t]he Tuesday next after the 1st Monday in November… This provision, along with 2 U. S. C. § 1

(setting the same rule for electing Senators under the Seventeenth Amendment) and 3 U. S. C. § 1 (doing the same for selecting Presidential electors), mandates holding all elections for Congress and the Presidency on a single day throughout the Union.”

If an election is consummated after Election Day, this also violates the statute, and such behavior, along with State legislation that encourages it, is preempted by 3 U.S.C. § 1. The logic of such a prohibition goes directly to the heart of the evils Congress sought to nullify by creating a uniform Election Day. The Foster opinion discussed this as follows:

“While the conclusion that Louisiana’s open primary system conflicts with 2 U. S. C. § 7 does not depend on discerning the intent behind the federal statute, our judgment is buttressed by an appreciation of Congress’s object

‘to remedy more than one evil arising from the election of members of Congress occurring at different times in the different States.’… As the sponsor of the original bill put it, Congress was concerned … with the distortion of the voting process threatened when the results of an early federal election in one State can influence later voting in other States…”

Single day elections curtail a distortion of the voting process by concealing results that might influence later voting. The “object” of 2 U.S.C. § 7, as noted by the Supreme Court, was to remedy multiple evils involved with non-uniform voting. Therefore, under the unanimous holding in Foster v. Love, federal elections consummated before, and after, Election Day, are preempted by Congressional statutes.

A 9th CIRCUIT CASE THAT INTERPRETED FOSTER V. LOVE

In Voting Integrity Project v. Keisling, 259 F. 3d 1169 (2011), the 9th Circuit reviewed an Oregon statute that allowed early voting by mail, holding that nothing in Foster v. Love prohibited early voting, as long as the election was not consummated until federal Election Day. While Oregon allowed early voting, well before Election Day, unlike the Louisiana case, Oregon also continued voting on Election Day, the same day the election was decided.

The 9th Circuit took notice of federal statutes that require the States to accommodate absentee ballots, which inherently require multi-day early voting, holding that 2 U.S.C. § 7 did not conflict with early absentee ballot voting, because the evils of early voting were not encouraged by it, since the results of early voting were not released to the public until Election Day, and therefore could not influence later elections. The 9th Circuit assumed Congress intended both statutes to co-exist.

Whereas, there are no Congressional statutes that allow voting after Election Day, with the sole exception, noted by the Supreme Court in Foster, pertaining to the provisions of 2 U.S.C § 8, which allows the States to hold elections subsequent to federal Election Day, when there has been “a failure to elect at the time prescribed by law…” The Court referred to a subsequent election, under 2 U.S.C. § 8, following a failure to elect, as a “run-off”, and there attached discussion upon the legislative intent of 2 U.S.C. § 8 in Footnote 3, which states:

“The only explanation of this provision offered in the legislative history is Senator Allen G. Thurman’s statement that ‘there can be no failure to elect except in those States in which a majority of all the votes is necessary to elect a member.’ Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess., 677 (1872). In those States, if no candidate receives a majority vote on federal election day, there has been a failure to elect and a subsequent run-off election is required.”

While run-off elections are allowed under section 8, the statute itself does not adopt the term “run-off election”. It simply allows that States may hold elections to fill vacancies, including where there is “a failure to elect”. For the most part, when 2 U.S.C. § 8 was drafted, elections were far more simplistic, and the populations much smaller. Regardless, there is nothing limiting “a failure to elect” vacancy to exclusively encompass situations where neither candidate received a majority of the vote.

It’s important to note here that early voting helps reduce the stress on a State’s electoral process, by pre-canvassing ballots in advance. This makes it much easier for a State to make a final selection on Election Day, whereas elections consummated after Election Day contribute nothing to electoral efficiency and are subject to many of the same evils as multi-day voting.

Commenting further on Foster v. Love, the 9th Circuit stated:

[W]e have a Supreme Court decision which we must follow, explaining that the word ‘election’ means a ‘consummation’ of the process of selecting an official…The Foster definition of ‘election’ implies that there is only a single Election Day in Oregon, when the election is ‘consummated,’ even though there are prior voting days.”

The 9th Circuit interprets Foster v. Love as mandating that the word “election” means a final selection of an official on Election Day.

CONCLUSION

Consider all of the above in light of the results of the 2020 presidential elections; in Pennsylvania today, two weeks after Election Day, 8000 votes suddenly appeared, and the initial count is still not complete; Arizona has tens of thousands of ballots left to count in the initial canvass; Georgia discovered over 2600 missing votes yesterday, and the entire State is conducting a recount; Wisconsin just announced the details and costs of a forthcoming recount; Michigan is buried in litigation supported by many sworn affidavits alleging irregularities. None of these states consummated their elections on November 3rd. The elections have failed, as a matter of law. The results should be voided.

Reading Foster v. Love, together with the 9th Circuit’s analysis in Voting Integrity Project v. Keisling, we know that consummating an election before federal Election Day is prohibited, and that early voting is not prohibited, as long as the election is finally consummated on Election Day. If that be the case, then statutory construction makes it obvious that elections consummated after Election Day are preempted by the federal Election Day statutes.

Any other construction would render the statutes inoperable. If “the election” – which is defined in Foster v. Love – as the combined acts of voters and officials – begins before Election Day, then continues after Election Day, there is no real Election Day. The statute would be utterly inefficient, and the plenary authority of Congress over the time to choose electors would be denied. There is no possible construction of the statute which would allow State elections for presidential electors to continue after Election Day.

3 U.S.C. § 1 states: “The electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed, in each State, on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November, in every fourth year succeeding every election of a President and Vice President.”

The electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed on Election Day. They weren’t. Elections were held. Midnight came. No elections were consummated. Two weeks later, they remain unconsummated.

Failure to elect triggers:

3 U.S.C. § 2. Failure to make choice on prescribed day

“Whenever any State has held an election for the purpose of choosing electors, and has failed to make a choice on the day prescribed by law, the electors may be appointed on a subsequent day in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct.”

Whereas, 2 U.S.C. § 8 allows for another election to fill a Congressional seat when there is a failure to elect, 3 U.S.C. § 2, simply reiterates the power of the State Legislatures to choose the electors. The statute is required to extend the deadline. It grants an exclusive courtesy to the Legislature, and nobody else. It voids the election facially in the title:

“Failure to make a choice on prescribed day.”

A Void Elector In Rhode Island

We shall finish up with an example of how this concept works from the

State of Rhode Island: In The Matter of George H. Corliss, The American Law Register, Jan. 1877, pgs. 15-25. In Rhode Island’s popular vote for presidential electors in 1876, George H. Corlis received the most votes to become a presidential elector, but subsequent to the election it was discovered that he was ineligible to hold the office, because he held a U.S. Centennial Commission, making him an officer of the United States, and therefore ineligible to be an elector according to the Constitution.

The State didn’t know how to proceed, so the governor requested the opinion of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island. In a 5-0 unanimous decision, the Court informed Governor Lippitt that Mr. Corlis was ineligible. The Governor then wanted guidance as to whether the person who received the second highest tally of votes should be seated as an elector. The Supreme Court said no, stating:

“The only effect of the disqualification, in our opinion, is to render void the election of the candidate who is disqualified, and to leave open one place in the electoral college unfilled.”

Here is the federal statute relied upon to settle the matter:

“The law of the United States provides that ‘whenever any state has held an election for the purpose of choosing electors, and has failed to make choice on the day prescribed by law, the electors may be appointed on a subsequent day, in such manner as the legislature of such state may direct:’ U.S. Gen. Stats., p. 21, sect. 134.” (Same as 3 U.S.C. § 2)

So, there was a popular election, where the people made a choice, but the controlling statute clearly states that Rhode Island failed to make a choice. This is what happens when an election is void. It is as if there was no election at all, hence, no choice is said to have been made. The election was a nullity, despite other eligible candidates having received votes.

The final disposition was resolved by a previous act of the Legislature, Gen. Stat., ch. 11, sect. 5, a statute which provided that:

“‘if by reason of the votes being equally divided or otherwise, there shall not be an election of the number of electors, to which the state may be entitled, the governor shall forthwith convene the General Assembly at Providence for the choice of electors to fill such vacancy by an election in Grand Committee.’ We think this provision covers the contingency which has happened, and that, therefore, the General Assembly in Grand Committee can elect an elector to fill such vacancy…”

The candidate receiving the second most votes didn’t become an elector, because the entire election was void. There was a failure to elect at the time prescribed by law on Election Day. The Rhode Island statute covered the situation, because it kicked the decision back to the Legislature.

It’s crucial now that this argument gets to the United States Supreme Court. Multiple State elections failed to consummate their elections on Election Day and are now void. There is no election. The State Legislatures have exclusive plenary authority to determine the manner in which the presidential electors shall be appointed. But their road will be so much smoother if the Supreme Court voids the elections first. This strategy gives another pathway to a true Constitutional resolution.