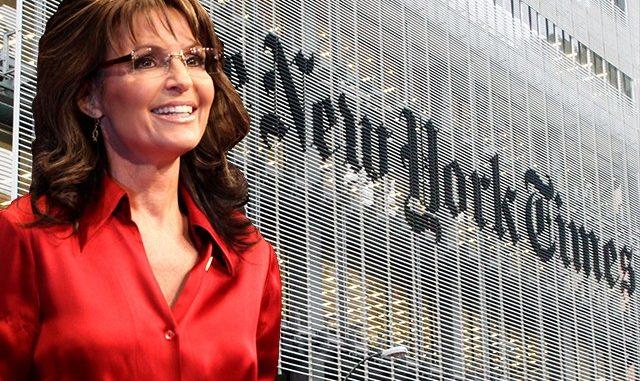

Sarah Palin is about to get all mavericky in court.

Indeed, the former Alaskan governor and vice presidential candidate just might be making new law in the area of defamation. Palin’s won a major victory in a decision by Judge Jed S. Rakoff, who ruled that she could go to trial o a particularly outrageous editorial by The New York Times In June 2017. The editorial suggested that she inspired or incited Jared Loughner’s 2011 shooting of then-U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, D-Ariz.

The case also involves a curious twist due to the involvement of James Bennet, who resigned in the recent controversy over an editorial by Sen. Tom Cotton. I supported Bennet’s decision to publish that editorial and denounced the cringing apology of the Times after a backlash.

This ruling comes after Nick Sandmann was able to survive motions to dismiss in his own defamation lawsuits and settled with various news organizations like the Washington Post over false reports of his confrontation with a Native American activist in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

These actions are likely to increase as media plunges headlong into “echo journalism” where stories are framed to reaffirm the bias and expectations of their readers.

The ruling concerns an editorial by the New York Times where it sought to paint Palin and other Republicans as inciting the earlier shooting.

The editorial was on the shooting of GOP Rep. Steve Scalise and other members of Congress by James T. Hodgkinson, of Illinois, 66, a liberal activist and Sanders supporter.

The attack did not fit with a common narrative in the media on right-wing violence and the Times awkwardly sought to shift the focus back on conservatives. It stated that SarahPAC had posted a graphic that put Giffords in crosshairs before she was shot. It was false but it was enough for the intended spin:

“Though there’s no sign of incitement as direct as in the Giffords attack, liberals should of course hold themselves to the same standard of decency that they ask of the right.”

The editorial was grossly unfair and falsely worded. Indeed, the opinion begins with a bang: “Gov. Palin brings this action to hold James Bennet and The Times accountable for defaming her by falsely asserting what they knew to be false: that Gov. Palin was clearly and directly responsible for inciting a mass shooting at a political event in January 2011.”

The Times stated “the link to political incitement was clear. Before the shooting, Sarah Palin‘s political action committee circulated a map of targeted electoral districts that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized cross hairs.”

In reality, the posting used crosshairs over various congressional districts, which included Giffords district.

The ruling represents a reversal of fortune for Palin after an earlier complaint was rejected. In Dec. 2019, Palin filed an amended complaint that just passed judicial muster. A three-judge panel reestablished Palin’s defamation claim in an August decision.

What makes this ruling significant is that it is focused on an editorial about a public figure. Both elements make it difficult to sue. Opinion is generally protected under tort law and public figures have a higher burden to bring any defamation case.

The standard for defamation for public figures and officials in the United States is the product of a decision decades ago in New York Times v. Sullivan. The Supreme Court ruled that tort law could not be used to overcome First Amendment protections for free speech or the free press. The Court sought to create “breathing space” for the media by articulating that standard that now applies to both public officials and public figures. In order to prevail, a litigant must show either actual knowledge of its falsity or a reckless disregard of the truth.

Simply saying that something is your “opinion” does not automatically shield you from defamation actions if you are asserting facts rather than opinion. However, courts have been highly protective over the expression of opinion in the interests of free speech. This issue was addressed in Ollman v. Evans 750 F.2d 970 (D.C. Cir. 1984). In that case, Novak and Evans wrote a scathing piece, including what Ollman stated were clear misrepresentations. The court acknowledges that “the most troublesome statement in the column . . . [is] an anonymous political science professor is quoted as saying: ‘Ollman has no status within the profession but is a pure and simple activist.’” Ollman sued but Judge Kenneth Starr wrote for the D.C. Circuit in finding no basis for defamation. This passage would seem relevant for secondary posters and activists using the article to criticize the family:

The reasonable reader who peruses an Evans and Novak column on the editorial or Op-Ed page is fully aware that the statements found there are not “hard” news like those printed on the front page or elsewhere in the news sections of the newspaper. Readers expect that columnists will make strong statements, sometimes phrased in a polemical manner that would hardly be considered balanced or fair elsewhere in the newspaper. National Rifle Association v. Dayton Newspaper, Inc., supra, 555 F.Supp. at 1309. That proposition is inherent in the very notion of an “Op-Ed page.” Because of obvious space limitations, it is also manifest that columnists or commentators will express themselves in condensed fashion without providing what might be considered the full picture. Columnists are, after all, writing a column, not a full-length scholarly article or a book. This broad understanding of the traditional function of a column like Evans and Novak will therefore predispose the average reader to regard what is found there to be opinion.

A reader of this particular Evans and Novak column would also have been influenced by the column’s express purpose. The columnists laid squarely before the reader their interest in ending what they deemed a “frivolous” debate among politicians over whether Mr. Ollman’s political beliefs should bar him from becoming head of the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland. Instead, the authors plainly intimated in the column’s lead paragraph that they wanted to spark a more appropriate debate within academia over whether Mr. Ollman’s purpose in teaching was to indoctrinate his students. Later in the column, they openly questioned the measure or method of Professor Ollman’s scholarship. Evans and Novak made it clear that they were not purporting to set forth definitive conclusions, but instead meant to ventilate what in their view constituted the central questions raised by Mr. Ollman’s prospective appointment.

There is however a difference between stating fact and opinion and the Times blew away that distinction in the rush to shift attention on political violence to Republicans like Palin.

What is not striking about the opinion is how the court clearly lays out the case for malice by Bennet, the key element under the New York Times v. Sullivan standard. The Court details how internal messages immediately raised the possibility of raising violence on the right.

The case addresses the more insular issue of whether a plaintiff must establish actual malice with respect to meaning as well as falsity. This addresses the use of words that may be misinterpreted as opposed to intentionally making false statements. The Court ruled that Palin will have to shoulder the burden on both meaning and falsity. That could generate further appellate fights.

I was also struck by how the court suggested that the later correction issued by the Times might be used by the jury to assume or discount malice. It is rare that such a correction would be raised as substantial evidence on intent:

The fact that Bennet and the Times were so quick to print a correction is, on the one hand, evidence that a jury might find corroborative of a lack of actual malice, as discussed later. But, on the other hand, a reasonable jury could conclude that Bennet’s reaction and the Times’ correction may also be probative of a prior intent to assert the existence of such a direct link, for why else the need to correct? Indeed, the correction itself concedes that Bennet’s initial draft incorrectly stated that there existed such a link. If, as Bennet now contends, it was all simply a misunderstanding, the result of a poor choice of words, it is reasonable to conclude that the ultimate correction would have reflected as much and simply clarified the Editorial’s intended meaning.

James Bennet gained national attention after he was forced to resign after pushing the Cotton editorial headlined, “Send In the Troops.” The op-ed discussed the basis for using troops to quell riots, which has been done repeatedly in history. The Times not only disgraced itself by abandoning its independence but promised to avoid such controversies in the future. (Later, some of the very figures who insisted that the op-ed was factually wrong — without having to explain that allegation — would push bizarre anti-police conspiracy theories). Bennet, who is being sued for bias in this case, was forced out for allowing dissenting conservative views into the paper this year. There is an irony that Bennet’s alleged bias against Republicans did not lead to a push for his removal but his merely publishing the view of a Republican led to his ouster.

The Palin case could create some major new precedent on issues like showing malice on the meaning of terms or words. It is also a standout as a defamation case going to trial on an editorial.