Authored by Guillaume Durocher via The Unz Review,

The coronavirus epidemic has been highly instructive. In the face of a looming early death for millions of citizens, Western States have entered a genuine crisis in which the Schmittian sovereign – who was always there lying in waiting – has reemerged into the open and taken all the measures deemed necessary, liberty and law be damned.

The nations making up the European Union are highly illustrative in this respect.

For starters, there was no unified European response.

Each nation having its own police and media/consciousness, each one adopted their measures in a haphazard and uncoordinated manner, although all tended towards a gradual escalation.

Jean Quatremer, Libération’s euro-federalist correspondent in Brussels, lamented:

“Up to now, it has been every man for himself. Italy, the epicenter of the European epidemic, was abandoned; Germany and France even went so far as to forbid the export of medical equipment, with no regard for solidarity.”

Admittedly that was two weeks ago and since then the Europeans have made some progress in getting their act together.

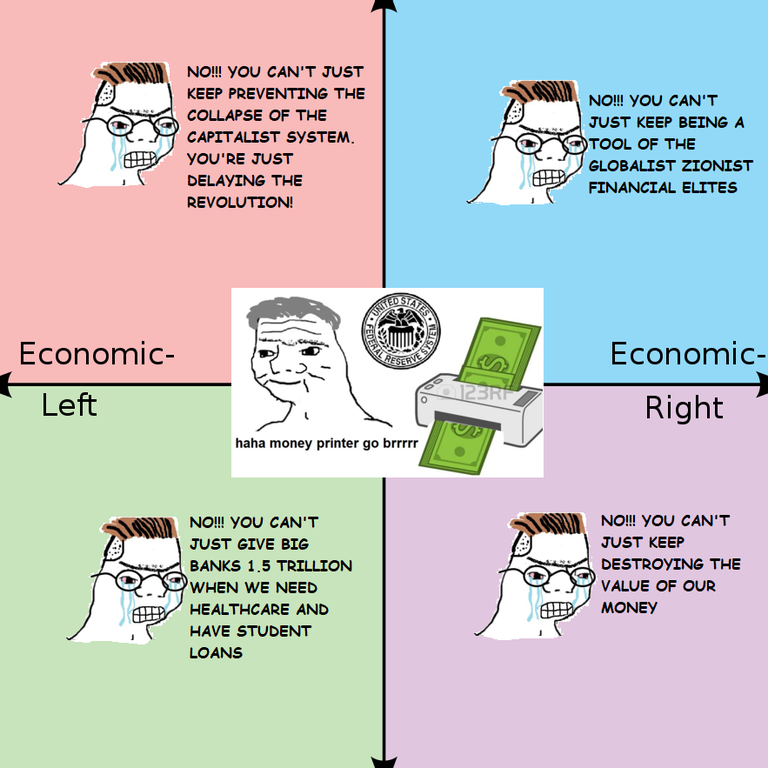

The European Central Bank (ECB) is perhaps the EU’s only truly federal and sovereign entity, in some respects more powerful than the U.S. Federal Reserve, because there is no pan-European political counterpart to counterbalance it. A few days after making the faux pas of declaring that the Bank’s job did not involve policing interest rate spreads, ECB President Christine Lagarde reversed her position and declared her institution would lend €750 billion to stabilize the European economy.

I am always left in awe of this spectacle: while European officials and lobbyists are locked in a perpetual struggle of niggardly Kuhhandel in Brussels over the pork-laden EU budget, Lagarde can summon up five times the annual budget with a snap of her fingers.

Corona really does work miracles.

Things that were declared “impossible” have become the norm. The parks of Western European cities are finally being cleared of migrants, now that these have been declared a sanitary hazard (being a criminal one was apparently not enough).

The European Parliament’s meetings in Strasbourg – a traveling circus which costs taxpayers €100 million per years – have been suspended. The EU’s balanced-budget rulebook, which the Germans fought so hard to impose over the last decades, has been thrown out the window. Each State is to borrow as it pleases to bail out businesses and provide welfare, at least for the duration of the national lockdowns. Individual liberty has been put indefinitely on hold.

In Italy, the number of cases and dead continues to steadily rise. As of 27 March, over 9,000 have died, including almost 1,000 just in the past day. Overwhelmed medical professionals have been forced to institute the grim practice of triage, choosing to concentrate on those individuals who have the best chance of survival and leaving many of the elderly to die.

Mankind only learns the hard way: one funeral at a time. A month ago, the mayor of Florence urged his fellow citizens to “huge a Chinese” in order to fight racism and xenophobia. Now Italian mayors are verbally abusing their residents to stay indoors in classic national style.

European States have adopted genuinely totalitarian levels of social control, affecting all citizens’ daily lives. In France, you cannot go into the street without a written declaration of your particular reason for being outside. Our countries have adopted a basically Mussolinian notion of collection liberty. As the Duce himself argued in his Doctrine of Fascism:

[Fascism] is opposed to classical liberalism which arose as a reaction to absolutism and exhausted its historical function when the State became the expression of the conscience and will of the people. [. . .] And if liberty is to be the attribute of living men and not of abstract dummies invented by individualistic liberalism, then Fascism stands for liberty, and for the only liberty worth having, the liberty of the State and of the individual within the State.

And, in truth, Western Europeans have by and large embraced the new measures. Huge majorities of over 85% support the national lockdowns in Spain, Italy, France, and Britain. With a typical “rally-around-the-flag” effect, leading politicians have also regained in popularity. French President Emmanuel Macron now has a 44% approval rating, a figure not seen since July 2017, while confidence in Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe has jumped by over 10 points since the start of the crisis, reaching 51%.

Our liberal democracies found their legitimacy on the sacrosanct equality and liberty of the individual, that is to say. Such doctrines and practices certainly thrive in peacetime but as soon as there is a real threat of death – an early death for millions of elderly Westerners, in this case – these notions melt away like snow in the morning sun.

In the face of genuine danger, the natural social condition effortlessly reasserts itself. Liberty, equality, and the “rights of man” naturally give way to the imperative of collective survival: Every man at his post!

In truth, collective organization in the face of imminent danger has been the norm throughout human history. Social prescription went far beyond mere politics to being part of something much deeper: custom.

There is a curious contradiction running across Western societies today. Over the last two-and-a-half centuries, we have seen the individual rebel more and more forcefully against the formal strictures of the group, against formal inequalities and restrictions on “private” liberty (for instance, buggery, harlotry, and spinsterdom). Any attempt to take action to reverse Western nations’ decline and save their ethnic and genetic identity is considered a “human rights violation.” At the same time, in practice, our citizens tolerate and often outright expect massive curtailment of their liberties, usually in the name of security.

The fascist critique of liberal-democratic ethics basically boiled down to a denunciation of selfishness and hypocrisy. As Ezra Pound complained in 1938: “In our time the liberal has asked for almost no freedom save freedom to commit acts contrary to the general good.” Indeed, Pound noted that as people had only known “the loose waftiness of demoliberal ideology,” one needed “sharp speech” to open minds.

Many have warned of the dangers of making individual entitlement the moral yardstick of nations. Gandhi, Heinlein, Solzhenitsyn, to name only a few, all tried to make the point their own way. Here is a lesser-known example, the Romanian anti-communist Petre Țuțea, who in the first years after the fall of Ceaușescu confused his freedom-hungry interlocutors by saying:

Communist totalitarianism is a contradiction in terms. Totalitarians can only be those people who from start from the whole to go to the part – according to the Aristotelian formula. [. . .] The [Communist] Manifesto’s end is final anarchy [. . .]. By their end, communists are anarchists.

Fascists, Hitlerians, and the Catholic Church are totalitarian, because they start from the Aristotelian principle: the whole comes before the part. These are totalitarians.

A journalist told me: You can’t say that, you are confusing the youth! I can’t broadcast that if everyone considers communists to be totalitarian . . .

But me […] I cannot take it back. I cannot lie.

It’s all well and good to understand that such a thing as civic virtue exists in times of crisis: that we are all in this together and must behave accordingly. But why does such Hellenic good sense not extend to peacetime?

Already today, civic virtue is highly unevenly distributed among the “French” population. Videos are circulating on social media of Africans and Muslims in France blatantly ignoring the confinement and social-distancing measures. According to Le Canard Enchaîné newspaper, the Interior Ministry responded by instituting “confinement lite” among this decidedly sensitive population.

This crisis is also an opportunity to reflect on the slow death of the Italian nation. I was raised near Italy and frequently visited the country growing up, gaining a real fondness for Italians and Italian culture. For me, crossing the Alps was like entering a different world, a different rhythm of existence. Today of course, with the Internet and the euro, the difference does not feel so great, yet still I love every second spent in the country.

Today, over 22% of the Italian population is over 65. The fertility rate of 1.32 per woman is among the lowest in Europe and is in continuous decline. While the Italians do not practice birthright citizenship and have not made it easy for non-European migrants to settle, there is still enormous pressure on the country from a continuous flow of illegals from Africa and the Middle East. We can ask: What will be left of Italy in 100 years? Not much, it seems, and that would be a great tragedy and a great crime.

There do not seem to be ten thousand ways of preventing the death of a nation.

Italy’s former Fascist regime fought for the country’s birthrate, power, stability, and economic independence. Emil Cioran – suspending his usual manic-depressive hyperbole – gave this qualified praise: “Overpopulation and Mussolini’s political genius have obviously raised [Italy’s] historical level [. . .]. Through Fascism, Italy suggested to itself that it become a great power. The result: she has succeeded in attracting the world’s serious interest. Nothing more.”

The citizens of the postwar Italian republic, that byword for the sleazy corruption of parliamentary politicians, have certainly enjoyed the fruits of consumerism. In the meantime, the country has steadily dwindled in significance, childless and aging, being reduced to a kind of debt colony of the European Union and international high finance.

The current polls still indicate a certain unpopularity for the Italian government, with a majority supporting a Right-wing coalition including conservatives and, especially, the nationalist parties Lega Nord and Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy).

The European financial system – that pyramid scheme of pyramid schemes – will emerge extraordinarily weakened from this crisis, as all the highly-uneven gains of recent years are lost with piling-ups of debt and reduced growth due to the coronavirus response. There are sure to be more crises.

Many globalists are afraid of what is to come. Joseph Borrell, the EU’s top diplomat, is worried China’s authoritarian competence will make Europe look bad. He opined on the European External Action Service’s blog:

There is a global battle of narratives going on in which timing is a crucial factor. [. . .] China has brought down local new infections to single figures – and it is now sending equipment and doctors to Europe, as others do as well. China is aggressively pushing the message that, unlike the US, it is a responsible and reliable partner. In the battle of narratives we have also seen attempts to discredit the EU as such and some instances where Europeans have been stigmatised as if all were carriers of the virus. [. . .]

But we must be aware there is a geo-political component including a struggle for influence through spinning and the ‘politics of generosity’. Armed with facts, we need to defend Europe against its detractors.

Personally, I’m not too worried about Chinese soft power. If Westerners look bad in comparison, that is only because of their own incompetence rather than the nefariousness of the Chinese. The Chinese State wants to make deals. The globalists want something much dearer: they want to bribe you into losing your national soul, your traditional values, your fighting spirit.

This crisis may come to be seen as the moment in which a declining and incoherent liberal-globalist West was geopolitically overtaken by an confident and organized national-authoritarian China. If so, we can also expect other countries may be tempted to change their political models.

For us Westerners, I’d arguer we don’t need to go so far afield for inspiration.